|

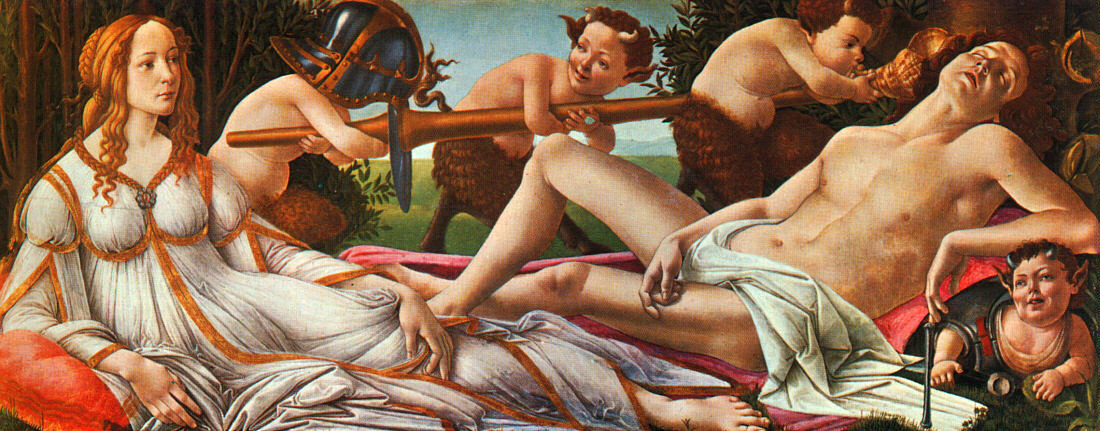

Botticelli's 'Venus and Mars' (c. 1485) is a

lighthearted look at the tug of war between men and women.

Men Are Mars, Women Are Venus

A Botticelli painting's timeless lessons on

male-female relationships and the differences between the sexes.

By HARVEY RACHLIN —

June 16, 2007; Page P16, Wall Street Journal

The 15th-century Italian Renaissance

painter Sandro Botticelli may be best known for his "Birth of Venus,"

but it is his "Venus and Mars" that really speaks to us today, brilliant

not only in its artistic virtuosity and beauty but in the way it

ingeniously renders in a single frame a vital message. Using

mythological figures, Botticelli's painting is a parable of the balance

of power between the sexes.

Venus gazes at a sleeping Mars after a

romantic interlude. She is draped in a flowing white gown, her curly

locks cascading gently over her delicate bosom, her body resting

casually against a soft apricot-colored pillow. The goddess of love

reigns supreme; she has subdued the god of war. Grinning satyrs play

impishly with the spoils of conquest. One has donned the war god's

helmet, wrapping his arms around the handle of the god's mighty spear;

another glances back at Venus to gauge her reaction to the sport; a

third mischievously puffs a deafening blast through a large conch into

the insensible god's ear; and the fourth, at the bottom, has crawled

saucily into the warrior's discarded armor. Mars slumbers deeply in the

sylvan glade -- surrendered of heart, depleted of strength, his

magnificent masculinity subjugated by the power of love.

Botticelli's lighthearted scene evokes

the perennial tug of war between men and women in a manner that brings

to mind a modern sitcom. Mars, his physical needs gratified, wants

simply to sleep; Venus, still wide awake, yearns for tender

conversation, for some indication that his interest in her is more than

sexual. Her ambivalent expression reflects a mixture of fulfillment and

wistfulness -- along with just a touch, perhaps, of smug satisfaction

that her charms have reduced the fearsome god of war to a lump of inert,

snoring flesh.

The painter delivers a vivid and

emphatic warning: No matter how great the passion, moments of blissful

union are fleeting. In Botticelli's vision of the power struggle between

the sexes, woman is stronger than man on the playing field of love. She

has stamina and strength; the exhausted man slumbers. But emotionally,

the woman's needs are greater -- so the man, oblivious to the finer

feelings, has more leverage. The leering satyrs suggest the artist's

sympathy for the woman involved with a man whose only interest is

carnal. When will Venus become bored with the war god's surfeit of

testosterone? For how long will the delights of sexual congress be

enough to sustain the relationship? Venus certainly doesn't seem to care

if the prankish satyrs succeed in disturbing her lover's slumber.

To the right of the sleeping god's head,

Botticelli has painted a wasps' nest, a poignant touch suggesting the

potential for a painful outcome to this relationship. Ironically, in

Roman mythology, among the offspring of Venus and Mars were a daughter,

Harmonia, the goddess of concord; and two sons, Phobos and Deimos, the

gods of fear and panic. And there is an even darker subtext: The liaison

of the goddess of beauty and the god of war was an adulterous one.

Vulcan, the ugly and misshapen god of the blacksmith's forge, maker of

weapons of war, was Venus's husband -- and the brother of her paramour,

Mars. The cuckolded deity would ultimately take his revenge, trapping

the faithless pair in flagrante in a net and dragging them to the

top of Mount Olympus to shame them before the other gods.

The Florentine painter's artistic jewel

strikes a chord in us today because it is a candid, honest and witty

reflection of the romantic aspirations, interactions, and realities that

we all learn the hard way. A droll visualization of the vicissitudes of

passion, it distills love's exaltations and nadirs, its accords and

confrontations, its pleasures and fragility into a single engaging

image. Aesthetically, Botticelli's genius is manifest not only in his

elegant technical rendering of the delicate details of wispy garments

and seminaked bodies, but in how he composed the intersecting legs,

drooping arms and sloping bodies in languorous lines to convey the

postcoital mood.

Painted about 1485, Botticelli's

romantic masterpiece, which now hangs at the National Gallery in London,

uncannily prefigures modern psychobabble concerning the differences

between the sexes. John Gray, in his best-selling "Men Are From Mars,

Women Are From Venus," codified as symbols of the idiosyncratic behavior

of male and female humans the two planets that bear the deities' names.

Today, countless books and articles echo the painting's themes, as well

as its rich nuances. It is a Dear Abby column on canvas, enlightening us

about the tensions inherent in the union of opposites, as current now as

it was half a millennium earlier when Botticelli created it.

Little is known about Botticelli's love

life. What experiences or impulses drove him to depict this scene on

canvas? Did he, like Mars, ever shed his armor and shield and helplessly

succumb to the overpowering enticements of love? Did the fate of the god

of war ever befall him? The artist, who painted religious subjects,

allegories and mythologies, was about 40 years old when he portrayed the

Roman deities. The circumstances for which Botticelli painted "Venus and

Mars" are not known, although it may have been as an adornment for the

bedroom of a patron.

But if Botticelli's fable of rapture and

its aftermath was a commissioned work, who was the patron? A man who was

psychologically secure enough to enjoy the reminder of women's power

over men? A woman who wanted to warn her lovers that she was not to be

treated as a plaything, to be used and tossed aside? Or did Botticelli,

in a puckish mood, present his unsuspecting benefactor with a subtle

commentary on the patron's own skirmishes with the opposite sex?

One thing is for sure: As long as humans

get caught up in affairs of the heart, Botticelli's "Venus and Mars"

will resonate with romantics and art lovers alike.

Mr. Rachlin is the author of "Scandals, Vandals, and da

Vincis: A Gallery of Remarkable Art Tales." |